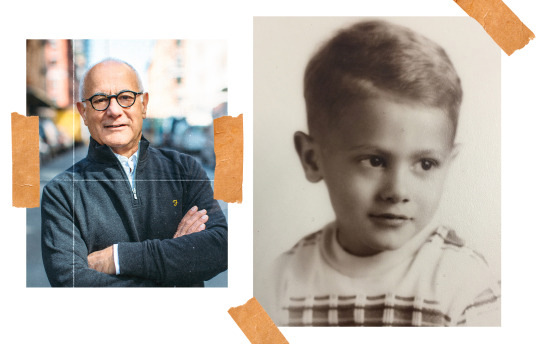

JIM FARAH

By Josh Sims

What’s in a name? How about Jim Farah? That’s right - Jim is the grandson of the man who founded Farah back just over a century ago. So we took the chance to sit down with him at home in New York to talk about his memories of the family firm which he’d eventually come to head up…

“When dad wanted us all to get up early he’d blast ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’ through the house,” laughs Jim Farah. “He was a big believer in us all getting involved with the business, in building a culture of respect for those who made the clothes. So if it snowed us kids didn’t get a snow day off school. We’d be at the factory early scraping the ice off the steps. You found yourself doing janitorial work.”

Jim Farah has strong childhood recollections of the family business: it was his Lebanese grandfather Mansour, a dry goods merchant and hay broker who had come west via Canada, and his grandmother, the second of 16 children of a Greek orthodox priest, who founded Farah in El Paso, Texas. This was about a century ago, in 1920. He saw a future in wholesaling rather than retailing, with the focus on making hard-wearing work shirts and accordingly set up a business specialising in their manufacture.

Mansour died in 1937, 10 years before Jim was born. But Jim’s grandmother, father and uncle - not to mention other members of the Farah clan - built on his grandfather’s hopes for the business. Jim Farah’s earliest related memory is, aged four, wearing an outfit made by the Farah Apparel Co - cuffed jeans and a denim jacket, complete with decorative panel into which was set a plastic stone. He remembers the music that would be played over the factory floor loudspeakers, over-laying the constant clattering of dozens of sewing machines.

“The family and the company were so intertwined that going to the factory was something we did naturally and often,” says Jim, who was born in El Paso but has lived much of his later life in New York. “When I was older I’d man the telephones at the weekend, which meant operating one of those old-fashioned plug-in switchboards, as we’d think of it being now. I always felt very intimidated about pronouncing all the Latin American names properly.”

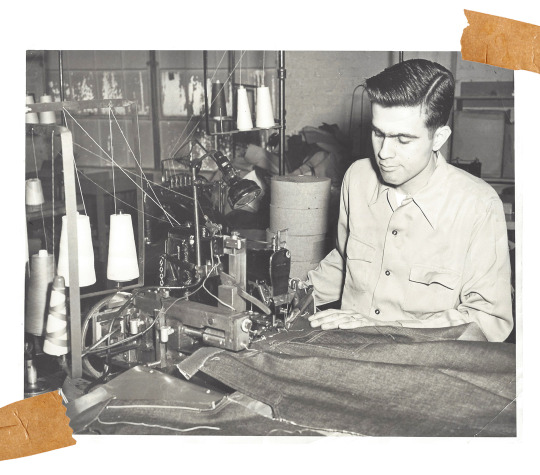

As a result of this intertwining, it was perhaps inevitable that Farah would end up working for the company himself. His father William, who died aged 78 in 1998, had followed a like path: attending a local college before joining up (with the interlude of World War Two, during which he served as a bomber pilot and instructor, while the business took a government contract to make uniforms). When William’s brother, ‘Uncle Jimmy’ to Jim, died of a heart attack - “it happened at the factory actually,” says Jim, matter-of-factly - William told his son it was time he played a bigger part.

“He said I’d have to start going to work with the company every day after school because I was now next in line to take over,” recalls Jim, who would rise through the company to become its president, until he left in 1987 to manage other clothing brands. “Association with the business was pretty intense as a member of the family, but I think I probably had a choice whether or not to join [it]. And it seemed pretty compelling to me to be part of it.”

The business, like any other, always had its ups and downs. But one crisis turned out to be rather fortuitous though. The Texas prison service started its inmates on making work shirts, undercutting the price of Farah’s - so Mansour moved the business into making trousers. It would be one later style of trouser that would make the company’s fortunes, of course, and allow it to go public in 1967.

Jim’s father was also remarkably progressive for the times: the US factory had its own cafeteria and medical facilities; he’d ride a bicycle up and down the production lines, almost exclusively operated by women, all the faster to keep an eye on things; he invented machinery that automated the addition of belt loops and zips to trousers; he experimented with new fabrics, mass-producing, among other styles, polyester leisure suits - a huge hit at the time, something akin to the sweatpants and hoodie of their day. The Farah company would, Jim says, become one of the biggest men’s trouser manufacturers in the US, rivaled only by Haggar and “a company you may have heard of,” he jokes, one Levi Strauss - also then both family-run firms.

After World War Two the then Farah company somewhat re-created itself as a manufacturer of jeans, making private label products for major US department store retailers the likes of Sears, J C Penny and Montgomery Ward, before launching its own ‘Farah of Texas’ and ‘Gold Strike’ labels - the latter a success in large part because of the company’s creation of another machine that allowed a double knee section to be stitched (rather than just glued) in.

It was, of course, the creation of our hopsack pants that really set business booming. “For a couple of decades the company fought tooth and nail to win market share in the bottoms business,” says Jim. “But I think the company was clever in spotting the market for what was, in effect, non-denim jeans - a style that was casual but a little smarter than standard jeans, that was still very durable thanks to the way they were woven and, because of the way they were cut, which were more comfortable and cooler than just normal pants.

“Dad knew who the competition was. He added that ‘golden F’ tab in reference to Levi’s red tab,” adds Jim. “He always wanted to keep what we produced as elevated as possible and didn’t really want to work with denim. So the hopsack pant was a great alternative. And it worked. In the peak years of the late 1970s I remember figures of 30 million pairs a year being spoken about.”

The company, Jim concedes, “certainly missed the market a couple of times” over the decades - keeping up with a new world of ever changing trends wasn’t easy. “But our business was generally not about being super creative - after all, there’s a limit to how different an Oxford shirt can be. You can’t add an extra sleeve,” laughs Jim. “It was always more about ageless products with a certain cool factor, but also with a real focus on the importance of fit. It was because we’d had experience of making jeans that we got the fit so right on the ‘dress jean’ that was the hopsack pants. And that set a culture of commitment to fit at the company, which gave us a competitive advantage.

“You can say that about the Farah company as it is today too - I’ve just bought a Farah Oxford button-down myself and what makes it still is that it’s not tight, not baggy, but just right,” he adds. “I still wear the brand as much as I can.”

Hinterlassen Sie einen Kommentar